Short Answer: No. Probably not.

I call this one "the McBaby." Should I try to patent it before McDonald's does?

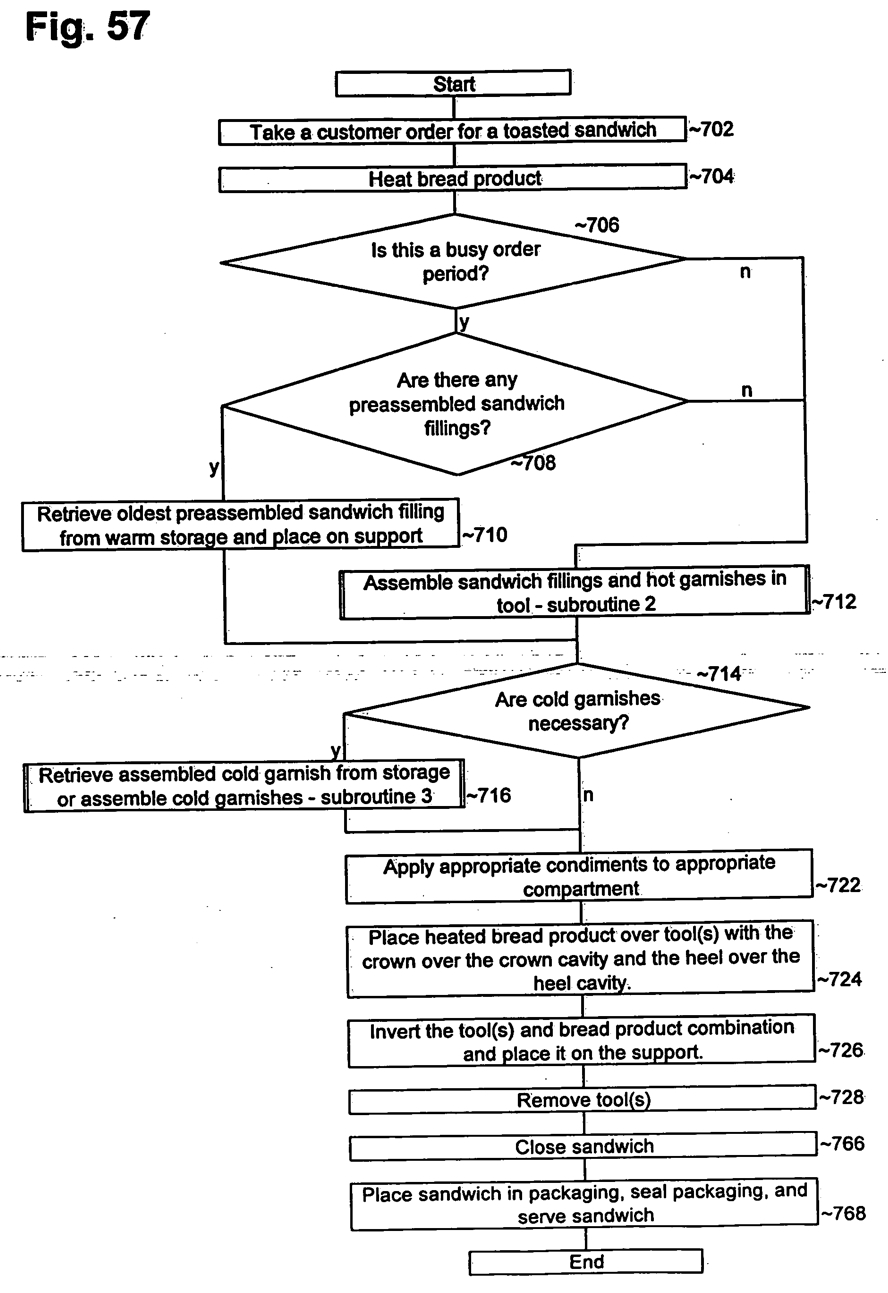

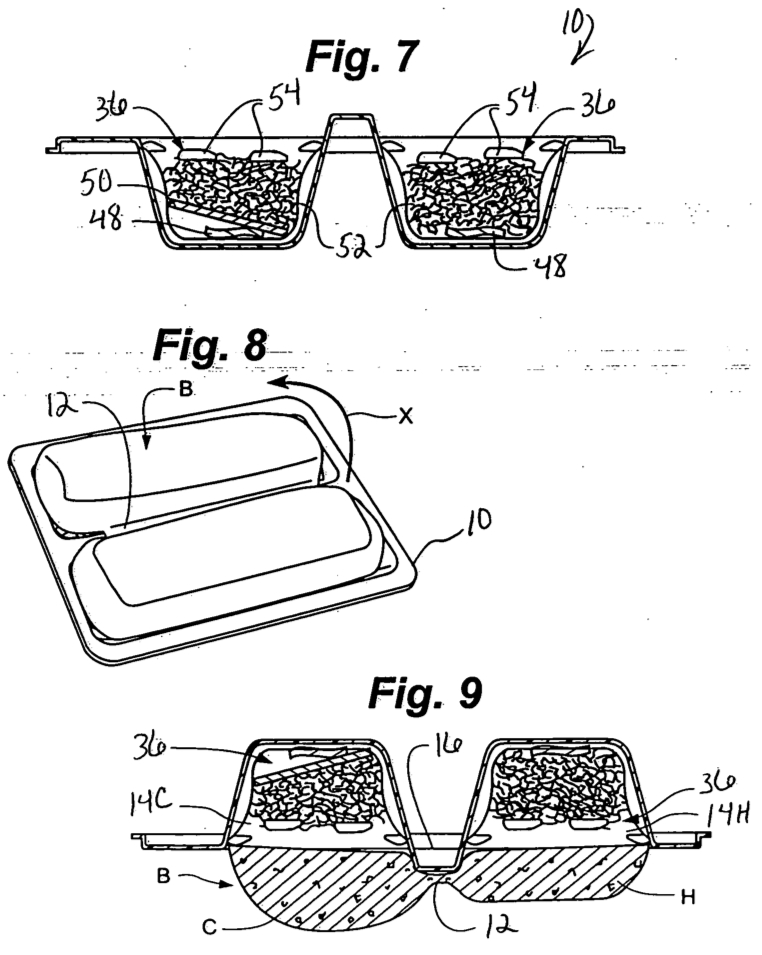

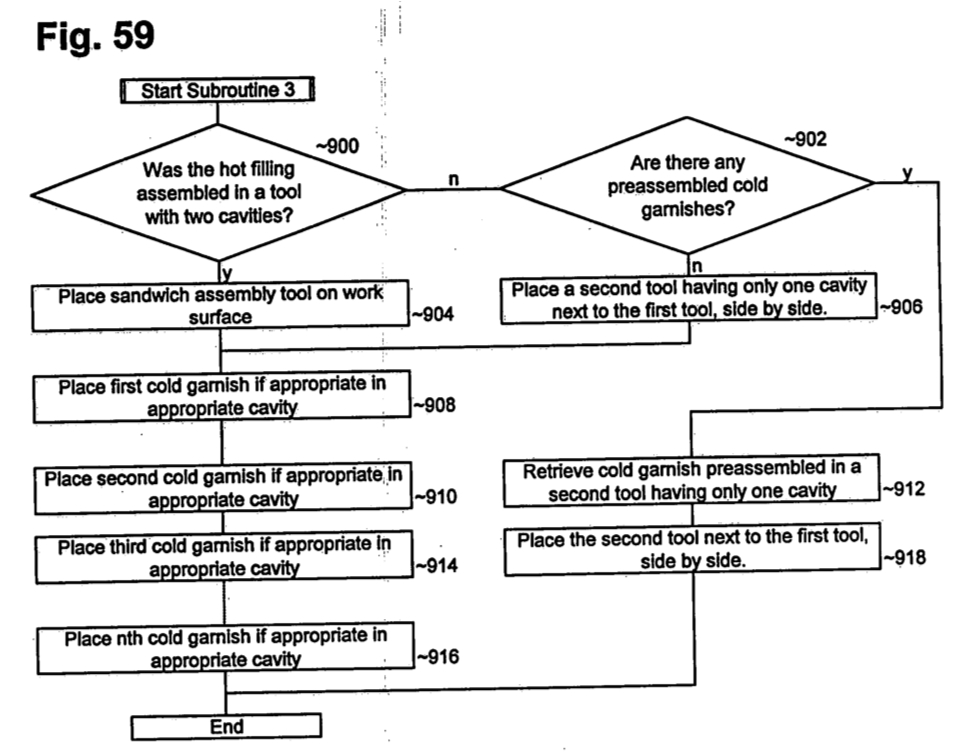

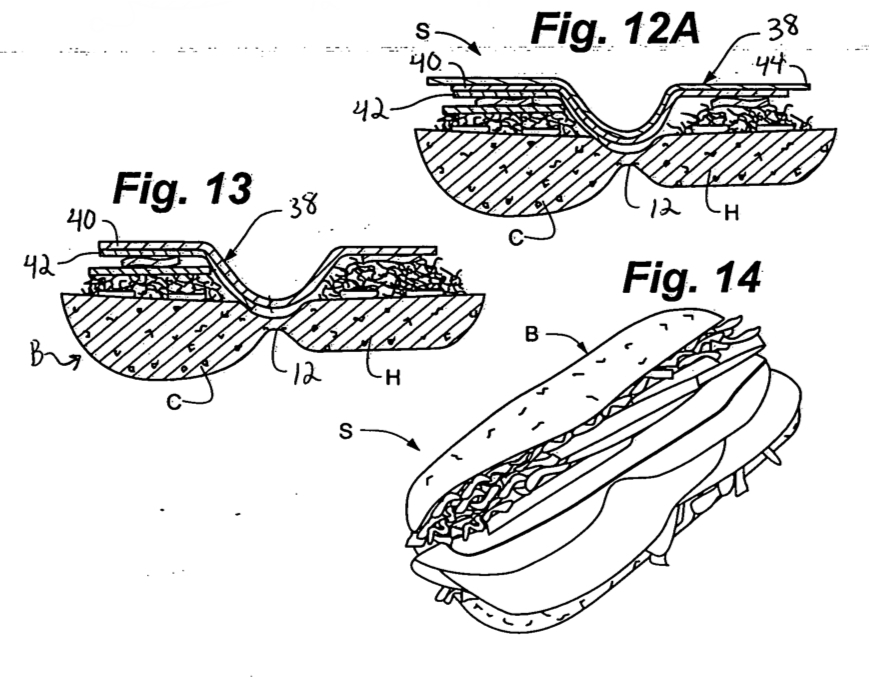

McDonald’s Corp. is getting some recent attention in the blogosphere for a patent application, originally filed in late 2004, which describes its “Method and Apparatus for Making a Sandwich.” What’s interesting to me about this news item is the array of different reactions that various people have to this kind of story. Personally, it makes me laugh that McDonald’s paid a patent attorney an ASS-ton of money to write and prosecute a fifty-four page app, comprising twenty-three pages of drawings and flow charts and describing, in painful detail, how one might go about simultaneously preparing sandwich garnishes while “heating a pre-assembled meat and/or cheese filling”. Clearly, my reaction is the same as the folks’ over at PatentlySilly.com.

The other response that I quite frequently see is one of outrage or consternation. “How can they claim a patent for that?” “Will they be able to sue me for how I make my sandwich?” “This is what’s wrong with the U.S. patent system.” “Yadda, yadda, yadda.” “I love lamp.” You get the idea. This was Marc’s reaction when we had a conversation on the subject a few days ago. Now I don’t mean to criticize or belittle anyone who has this initial reaction (obviously, Marc is no IP n00b), but it exposes the reactor as someone who doesn’t have a firm grasp on the intricacies of patent law. This is nothing to be ashamed of, because the majority of the world doesn’t either. Without digging into the details of each individual case, it’s easy to go off half cocked.

So, rather than writing a blistering piece about how arrogant corporations abuse intellectual property (the story that Randazza might have written), I was inspired to use this particular example as a teaching vehicle to hopefully clear up some commonly held misconceptions about patents. It is also a useful exercise for me to try explaining this material to a general audience that does not have a background in hard-core intellectual property law.

By way of disclaimer, I am not a practicing patent attorney (yet). However, I do have the benefit of sitting through several courses on U.S. and international patent law, as well as a five-week summer associate gig working with the electrical engineering patent group of a large law firm (special thanks to the Atlanta office of Ballard Spahr Andrews & Ingersoll, LLP – formerly known as Needle & Rosenberg, PC). If anyone reading this post happens to be an expert in patent law, I encourage you to sound off in the comments if I get anything wrong or you don’t agree with my analysis.

The Sandwich App – U.S. Filing

McDonald’s filed their initial application for patent with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) on December 21, 2004. As stated above, the app described an “Method and Apparatus for Making a Sandwich.” Clearly, much care and effort were put into preparing the voluminous document, which more than reasonably describes an important business practice of any fast food restaurant – making burgers (or sandwiches, or burritos, or gyros) as quickly and efficiently as possible – and a “tool” for making that happen. Both the tool and the method are proper subject matter for patent protection in the U.S., provided that they work as expected and are novel and non-obvious. If they really had something, McDonald’s is far from crazy for seeking the competitive advantage that patent protection would provide by allowing them to prevent other fast food chains from making their sandwiches the same way. No one should doubt their credentials as experts in the field of sandwich making, given their commercial success and significant global presence. If anyone was gonna innovate in this area, McDonald’s is on the top of the short list, much like Intel would be for microprocessors.

The United States government, way back when they were trying to figure out how everything should work here (circa late 1700s), decided that the best way to facilitate advances in knowledge and technology was to provide a mechanism that encourages smart people to share their ideas with the world in exchange for the right to control, for a limited time (currently, twenty years), who could practice the devices and methods embodying those ideas. This “exchange” is symbolized by a patent. Think of it like a contract between the inventor and the government.

The inventor agrees to write a document (the application) that teaches his colleges all about his or her invention, and in consideration, the government recognizes the inventor’s right to profit from his or her invention. This quid pro quo ensures that brilliant ideas are not kept secret for competitive advantage and that the collective knowledge about useful things continues to grow. This way, another smart person may read about an idea and say, “I can do it better/cheaper/faster.” Thus the progress of science and the useful arts marches forward.

Turning back to our “Sandwich” application, in order to qualify for patent protection, the app must disclose something that is useful, new, and non-obvious. To make that determination, the USPTO assigns the application to an examiner, who presumably has some expertise in this field of endeavor (in this case, Art Unit 1794, Class 426 – “Food or Edible Material: Processes, Compositions, and Products“). The examiner’s job is to research the technology and find out if McDonald’s has truly added something new to the art of sandwich making.

In this particular case, the examiner’s first response was to tell McDonald’s that their application disclosed multiple “inventions.” Multiple inventions mean multiple patents, so McDonald’s was forced to pick which one they wanted to pursue first (commonly called a “restriction requirement”). They opted (or “elected” – in patent-ese) to go after the method claims first, leaving the sandwich-making tool for a later “divisional” application, and the examination process continued.

Now that the examiner knew which invention to work on, he got down to it, researching the relevant field to find out if McDonald’s had really discovered a new way to make sandwiches. After doing so, he concluded that they had not and sent a letter to their attorney (typically called an “Office Action”) that described his reasons for coming to that conclusion, providing citations to materials that support it. In order to proceed, McDonald’s will have to respond to the Office Action, arguing why the examiner was wrong or changing their “claimed” invention to something that actually is new and non-obvious. They never did so, and the application went abandoned earlier this year.

Quick, honey, call our attorney. I've invented the McPizza!

McDonald’s may have decided for any number of strategic reasons not to continue prosecuting the application. My guess is that they realized they were facing an uphill battle and preferred to cut their losses (which were probably significant at that point – between filing fees and attorneys’ fees).

The Sandwich App – International Filing

By nature, patent protection is a territorial animal. The foregoing discussion described the events that took place when McDonald’s attempted to obtain patent protection for the United States only. If an inventor wants protection in other countries, he or she has to go through a similar process for each country where the inventor wants to enforce his or her rights. This can be an extremely tedious and expensive process, which is made marginally less so through something called the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT).

The PCT represents a collection of over one-hundred countries around the world that have somewhat similar requirements for patentability. By filing a special application in an appropriate member country, an inventor can obtain an initial clearance for his invention in the form of a preliminary search for materials that would make the invention unpatentable. There is no guarantee that a clearance from the PCT search authority means you will be able obtain patent protection in each and every designated country, because each country has its own unique requirements. The local PCT office just acts as a single point for filing your initial application and as an initial search provider for things that will present clear barriers to patentability.

On the PCT application, the inventor chooses which countries he will pursue patent protection in, once the initial clearance is done. After it is completed, the preliminary search report is transmitted to each of those designated countries, and the applicant must continue the prosecution of the application with each of the local patent offices – commonly called “entering the national phase” for a particular country.

Although the PCT filing fees are capped after the inventor has chosen more than a few countries, the local prosecution fees for entering the national phase of each designated country can pile up pretty quickly. As a result, it is rare that anyone would chose to pursue protection in more than a few member countries. In the case of the Sandwich App, McDonald’s chose the U.S., Canada, Australia, and the European Union.

I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking that the European Union is more than one country. That’s true, but they have their own special procedure that is available for applicants who want to secure protection in multiple European countries. It is similar to the PCT process, except that, where the PCT search authority is only able to do a preliminary search for materials that could potentially prevent the issue of a patent, the European Patent Office (EPO) is able to prosecute the application all the way through to “allowance.” However, there is no such thing as a “European Patent.” So once the EPO gives its go ahead, the applicant must take his or her clearance from the EPO to each of the European countries in which the inventor wants to assert his or her rights, file a translation of the application (if required), and pay the local issue fee. Here again, the more countries you pick, the more expensive the process gets.

The McWTF Sandwich (available for a limited time, only at paticipating locations, patent pending)

Finally, returning one last time to our Sandwich App, a preliminary search was done by the USPTO (as the local PCT search authority) and sent out to the various national patent offices on April 9, 2009. Not surprisingly, the report listed the same documents found by the original U.S. examiner, which indicated that the invention was not new or non-obvious.

The Canadian application had fees due in December, 2008, which were not paid by McDonald’s. Presumably, this means that, like the U.S. patent application, they have decided to abandon the Canadian one. With the U.S. and Canada off the table, I’m guessing that McDonald’s has foregone patent protection for their method of sandwich making in the largest portion of their market. While they still may pursue protection of their sandwich-making tool in the U.S., one might question the business decision-making ability of the McDonald’s exec who finds it prudent to throw good money after bad.

The Australian application is awaiting a final determination, but it seems unlikely that the Australian Patent Office will come to a different conclusion than the USPTO.

Interestingly enough, McDonald’s paid a fee to the EPO in January, 2009, keeping the European application alive for the moment. Again, however, I have a hard time believing that the EPO will come to any different conclusion than the USPTO.

Conclusion

So, long story short (too late, I know), McDonald’s isn’t likely to sue anyone for infringement of this “invention.” Because they haven’t really demonstrated that their “discovery” adds anything to the field of endeavor, they haven’t held up their end of the “contract” that would entitle them to patent protection. The system worked as expected, and patent protection was not extended to what amounts to no “invention” at all.

This story was originally published on The Legal Satyricon.